Simon Ogden | Dancing on Quicksand

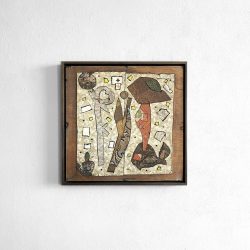

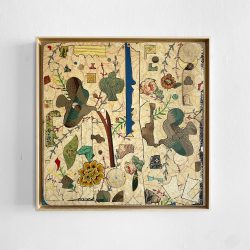

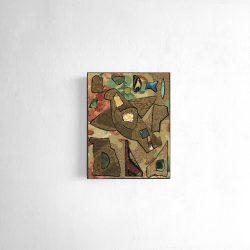

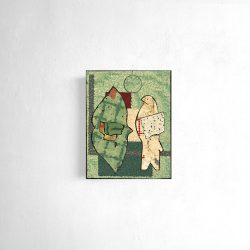

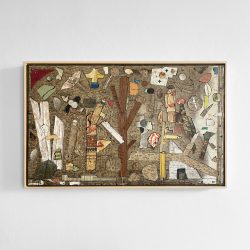

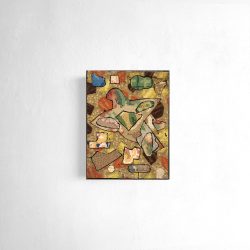

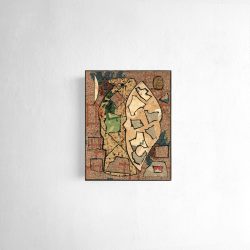

Dancing on Quicksand is Simon Ogden’s latest exhibition in Tamaki Makaurau. His practice encompasses painting, printmaking, assemblage and sculpture and is one of the few artists in the world working with antique and ‘found’ linoleum to produce striking landscapes. The exhibition comprises a new series of linoleum constructions, presented alongside found object assemblages and painting. The intersection at which these approaches meet is at the heart of Simon’s practice which explores the interplay and transformative power between media, object and form.

Simon Ogden | Dancing on Quicksand

by Bronwen Neil, FAHA, Professor of Ancient History, Macquarie University

“It was a privilege to spend some hours with the artist recently in his home and studio in Christchurch. The stillness of the garden, a verdant space redolent with herbs and small sculptures, new grapes dangling from the vines overhead, is the perfect frame for the production of Simon Ogden’s latest exhibition: Dancing on Quicksand

Ogden has long attracted interest for his bold use of colour and sculptural forms. One of the pieces showcased in his private collection of Modernist works from the 20th century was created by his mentor. Peter Grieve used small human figures in brass, a lead parachute, and a Ferris wheel constructed from recycled wood and wire to reconstruct a dream sequence. This sculpture is kinetic even though it has no moving parts. The same sense of tightly coiled potential, a sort of momentarily stilled life, caught in his representation of everyday objects, flora and fauna, characterises this latest exhibition as a whole.

Simon grew up in the English North and moved to London to pursue a Foundation year in Carlisle College of Art and Design, followed by a Bachelor of Fine Arts, Sculpture, at Birmingham Polytechnic, and then a Master in Fine Arts at The Royal College of Art London. His regular haunts as a student and practitioner were the V&A, and – during the period that he was employed by the Westminster council as a road sweeper around the National Gallery – the basement of that house of art, where hundreds of medieval objects were housed.

Wooden statues of saints, stained glass in French and English churches, some of them reconstructed from the sherds left by the shattering wars, all contributed to his unique aesthetic. Today he favours sculptural shapes, some of which are recognisable from the natural world (moths, roses, peonies, birds, trees, suns and moons). Humans are occasionally represented by synecdoche: lips stand for a woman, for example, in “Seduction”; but these images are more subtle than the more intimate body parts depicted in Ogden’s erotic series of plaster cartouches from the 2010s.

One important way these nuances are achieved is through his use of a material that may seem to many mundane and symbolic of a Modernist approach to domesticity that is perhaps better forgotten. Linoleum was invented as a demotic alternative to more expensive floor coverings such as wood, tile, tapestry and later wall-to-wall carpet. Many viewers will recall lino as the dullish backdrop to our suburban childhoods. Popular in holiday homes, kitchens, laundrettes, hospitals and schools, it was durable, practical and flexible, but rarely beautiful.

It may come as a surprise, then, to learn that even in the late nineteenth century, linoleum could be a work of art in itself in the hands of a master printmaker such as William Morris. Central to the Arts and Craft Movement pioneered by Morris was the principle that ordinary working households should be able to enjoy beautiful objects and surroundings at home and at work, and that their work in producing such objects and surroundings for the wealthy should be valued.

A resident of Christchurch for some decades now, Ogden recognised the practical beauty of linoleum as an objet d’art and a vehicle for conveying layered social meanings. He set about recovering it from the floors of New Zealand homes, institutions and factories. He now holds a unique hoard of linoleum that was destined for the scrap heap. These source materials go back to the early 1900s. His collection of miscellanea for future use includes button cards in variegated sizes and colours; fragments of clay pigeons shot in local vacant lots; bits of driftwood and old building materials in wood, iron and bronze; doors and windows from doll houses and tiny tessera from dismembered mosaics, and even a remnant of an early linoleum design from Liberty in London. A range of linoleum samples serve as the ground for these new works, with designs ranging from delicate filigree and pointillism to bold expressions of modernism. The material is both literally and figuratively plastic, and when put together with other more earthy matter, such as wire, oxidised paint, or carbonised cedar framing, it takes on an other-worldly quality that makes it luminous.

Three pieces in this series – Grey Lynn Peony, Flying East & Blue Fall – are some the most sombre in Ogden’s oeuvre to date, featuring a khaki-and-green linoleum background that is vaguely reminiscent of army fatigues. Their muted tones are relieved, however, by flashes of primary colour. You don’t need to wonder if this was the product of enforced solitude during the recent lockdowns. They reflect the Zeitgeist of the pandemic and its aftermath – the sense that optimism is harder to come by now. Some of the other titles – ‘Fallen’ and ‘Falling’ – convey the impression of last glimpses of a lost world.

It is often noted that those who are far from their places of birth and home countries are often more attuned to some aspects of their adopted homes than the locals and can see things that are so familiar to locals as to have become invisible. Certain pieces stood out for me as a visitor: the cold stillness of a winter skyline at dusk (in Winter) transporting vistas but earthed in natural objects: a branch of cabbage tree flattened by a passing vehicle. The retrieval of abandoned and forgotten natural and synthetic objects – and their juxtapositions – make this work feel nostalgic, I think, as much as the way Ogden processes and beautifies the objects he has salvaged. In ‘Falling’, the samples from the University of Canterbury Christchurch of enamel-on-copper tests for silversmithing courses, run as part of the design curriculum during the late 50s and 60s, are lovingly displayed in a snowfall of parallel lines, complete with their hand-written tags. The ensemble of some fifty metallic objects within the frame is striking, the dark background of browns and blacks relieved by brilliant pinpoints of colour and a multitude of buttons stored for many decades on sample cards.

Long-term followers of Ogden’s work will see immediately see that this is something new, albeit with the familiar motifs. Ancient indigenous Australian artefacts, such as woomeras and striped wooden dancing sticks; budding flowers, dead trees, or rifles: the embedded linoleum cut-outs are polymorphous and have no single interpretation. For me, this multivalence makes these works feel rich with possibility: the recurrent standing bird and giant moth in ‘Blue Fall’ could spread their wings and disappear at any moment. There is an alluring open-endedness to them. The falcon-headed god Horus, part-man, part-bird, offspring of the Egyptian deities Isis and Osiris, hints at a religious depth to many of these pieces. One could call it an act of sacramentality – making ordinary objects holy through ritual – although this is not a word that Ogden himself would use. They somehow convey the gravitas of iconography.

Seeing the creator at work on this exhibition early in 2023 gave me a glimpse into the laborious and very solitary process required to produce these pieces, one with occasional moments of despair and frustration but generally underpinned and overlaid with joy. These emotions shine through in Falling and Fallen and illuminate the materials and their meanings. They invite us to look beyond the frame, to be transported to other places, different times, and new possibilities.”