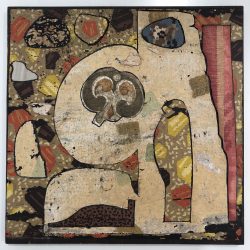

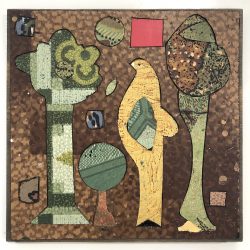

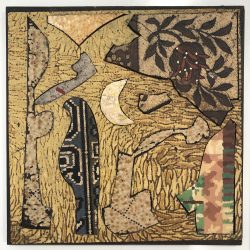

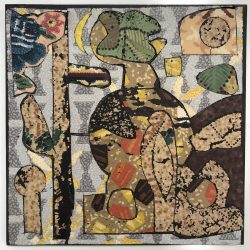

Simon Ogden | A Single Score of Many Parts ##12 Sept – 1 Oct

Essay by Damien Wilkins (2019):

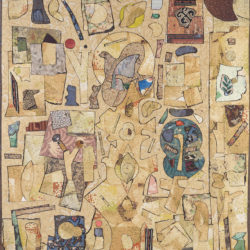

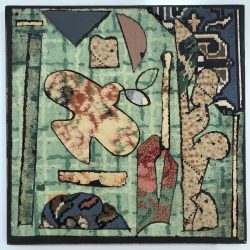

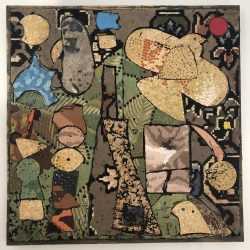

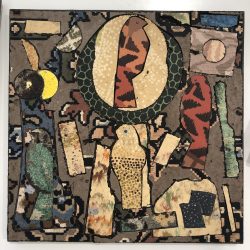

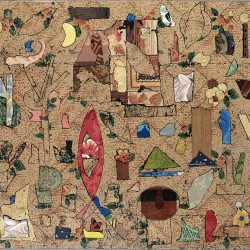

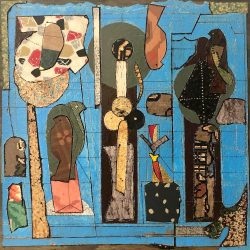

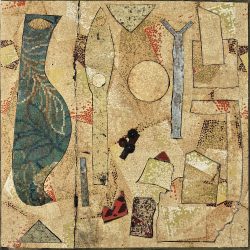

“The sandy-coloured, bird-filled world of Simon Ogden’s latest work might easily take us to ancient Egypt and the beaky scribbles of hieroglyphics. The Egyptians, poised at the beginnings of writing, saw in birds the power of communication: the image of an owl stood in for the sound of ‘M’; the quail chick was ‘O’ and ‘W’. I’m not sure if Ogden is writing to us using any phonetic system but his birds are certainly up to things. They perch and fly. They carry leaves. One has three eggs inside it. Some seem too ornately plumaged to ever get off the ground. Others are mere shadows, ideas of birds, sunk into the golden earth like delicate fossils. When our eye travels over this ground, away from the big colourful objects, it collects a wealth of odd fragments, some indicated by clearer shapes (branches, plants, stones perhaps), some only by shaded spots. Here is the partially-decipherable, shard-strewn landscape into which everything will presumably be smudged and rubbed out. Time will wear down the pencil of our world.

But surely that can’t be what Ogden’s luminous inscriptions are saying? They seem too light and airy for such a bleak message. They have—just as those cunning Egyptian artists had—a sort of anti-maudlin bounce. They are as weighty as we want but also communicate a cartoon levity. (It’s no accident that the museums of the world with Egyptian holdings seize on the hieroglyphs as a gateway for children to the ancient world. The line drawings of vultures and vipers are startlingly immediate across thousands of years.) The uncanny power of Simon Ogden’s work lies, I think, in precisely the way it enacts the drama of our mortal shuffle (from perch to dust) in terms that owe nothing to gloom or even melancholy. I wouldn’t say this latest banner work convinces us that it’s fun to imagine our own demise. Yet in its pictorial charm and its ingenious pattern-making, the work offers persuasion of a high order. It’s so pleasurable, while looking at this art, to submit to the basic idea that we—here I’m appropriating the birds as hieroglyphs for humans as well as pictures of themselves—are part of the bigger picture. And what is this picture?

I think it’s renewal. The cycling through life’s stages sure. From egg to egghead and back again. Also the way time sounds variations, prompts echoes, animates ghosts. The birds behind the birds behind the birds, and so on. How strange that the fossil of a bird flies over its living descendant! And we feel this too of course in the materials of Ogden’s art. His lino cut-ups are, even before the arrival of our metaphorical readings, doing this deep memory work since they revive the forgotten flooring of our ancestors. This art is not just ‘about’ reconfiguring the past; it is that past. But it’s the past retooled for a fresh purpose—and Ogden’s great colour sense helps enormously here.

I hope I’m not pressing too hard on all this fragile bird-life when I say that, finally, this work of patches and swatches of old commercial product (solidified linseed oil, ground cork dust, wood flour and canvas backing) presents us with a vision of the natural world as interconnected and interdependent, a quilted thing built up over layers of unimaginable time. That there are no human figures in it should give us pause. Wouldn’t we wreck this world with our boots, our curiosity? Anyway, the human epoch lies elsewhere. We haven’t arrived yet. Or maybe we’ve been and gone. Already finished. Though again, the work doesn’t feel tonally apocalyptic. Besides, the human lies in the invention of linoleum and, of course, in the hand of the artist who has knifed these beautiful shapes. So, yes, we’ve survived somehow.

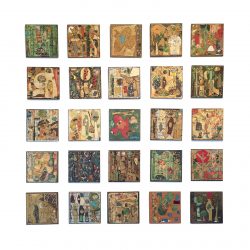

I used the word ‘cartoon’ earlier. I should also add that the austere grace of this created world is another aspect of its delight. It’s a rich visual vocabulary that can float such divergent impressions at the same time. And what to make of the frequently occurring circles throughout these panels? Moons that have cycled through the birds’ lives? Planets they’ve spied on clear nights? Holes for hiding in when it gets dark?”