Paul Woodruffe | Articulate Silences ## 2 – 22 July

Unlikely Punk.

No artists should ever be asked “why do you paint?”. It’s typically the imposter who will over explain why they paint and with self-confidence and no authenticity they will attempt to desperately justify what they do. Throwing a bunch of clever sounding words at art for the sake of complexity, to make it sound more “relevant” makes that art irrelevant and is an insult to the authentic artist. You can hurl the dictionary of obscurantism out of the window when you talk to Paul about art and his work. He has developed a systematic approach over years and a refined skill that is truly recognizable and alternative. His technique is disciplined, built out of many layers to create the iridescent colour planes that is open to a looseness and unknown. The complexity of his paintings carries its heft in the act of painting and the need to create. The concept or subject is secondary to the impetus and the outcome. I have heard another Auckland artist in discussion with Paul who agrees that it is the unexpected outcome that makes the act of painting meaningful.

It seems with Paul as with most artists of experience, stature, prestige and longevity there is no reason for “why paint?” – there is a resounding “must paint”. It is not a choice or a vocation, it is an obsessive compulsion. Paul paints because he must just like he needs to breath. How people respond to his work is their problem, price or prerogative. He’s not interested in being mainstream, to sell out to the fads of an industry or ideology. It is incorrect to label Paul as an “outsider artist” who operates off the centre, outside of the mainstream gallery system. Paul is an “outsider” only in as much as he is an artist that produces work that is located well outside the parameters of the expected. Paul is and always has been a PUNK.

He has primarily been an artist for most of his life and very much part of Auckland’s cultural landscape. You can ask Paul anything about art in Auckland over the last 30 years, he was there and has a story about it: Tony Fommison getting wasted in the corner of a gallery, the parties and drugs and music that fired up the New Zealand music and art scene of the 70’s and 80’s. Simon Grigg writes that the Auckland “scene developed in isolation from the equivalent scenes in London and NYC, simply because of the way the country remained shut behind a government enforced screen”[1] Paul was part of this cultural boom, the anarchism and struggle of artists who lived in studio spaces in abandoned or cheap buildings, just to make art. Very few people made money, but there was something meaningful going on. For a brief moment in time it was the playground for incendiary forces of a differing kind. All that punk rock shit, you know the historical gaze, the tight pants, the sneakers, ripped t-shirts, the fucking safety pins. The art school crowd, the working class dumbos, bad boys and good girls lost in a fantasy of their own making…”[2]

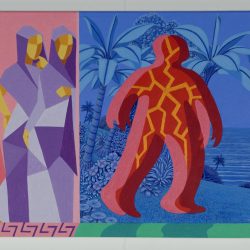

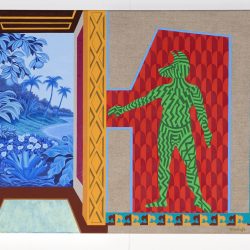

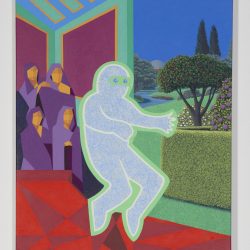

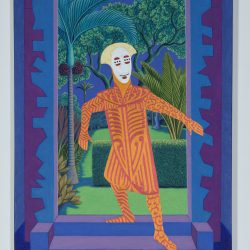

The energy and soul of Punk still reverberates in Paul’s paintings. Not in style or subject, but in the sounding lifestyle of unapologetic honesty and an informed opinion. That is very rare to come by. The punk is the one who is upsetting everyone because he challenges the status quo. One of the paintings called “The Artist” shows floating figure, that looks like it belongs in a vintage video game, floating between the angular and botanical space is on his own buzz and mental state, the onlooker not sure what to make of it. Voyeurs interested and distant. Philosopher Richard Kearney[3] writes that “the drive to fuse with the other is not always carnal, or even personal. The unconscious has countless ruses up its sleeve to transfer libidinal fixations onto sublimated, impersonal figures”.

The Artist has left the building and doesn’t care what you think. He is vibrating in his own bubble. He’s doing his own thing. The impersonal judgments or opinions of others are acknowledged in these paintings, while at the same time, dismissing their significance.

Flying

In 1968 people hysterically wanted to believe that the Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds was all about dropping acid. The fantastical imagery was attributed to a psychedelic trip. The journey to new realms of consciousness, asking you to “Picture yourself in a boat on a river, or at the train station, newspaper taxis Waiting to take you away”. However, the origin of the song came from childish innocence. It was inspired by Julian, Lennon’s three-year-old son who fancied a little girl in his class and made a drawing called “Lucy in the Sky with diamonds”. The Beatles simply had to write the song. Just like Woodruffe simply had to produce this show “Articulate Silences”. McCartney said in an interview that: “When you write a song and you mean it one way, and someone comes up and says something about it that you didn’t think of – you can’t deny it.

Articulate Silences, the title of his recent show, comes from a track off an album by Stars of the Lid. There is always music when he works in his studio. He listens to just about everything. The ambiance of sound is significant in his studio practice. Robert Fripp described the act of music existing in several worlds simultaneously. It can be said about the act of painting also. There are several planes of consciousness in paintings, their impetus, output and outcome.

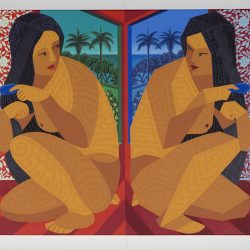

When Paul makes his paintings, they are not necessarily meant to mean any one thing, or to be understood in any prescribed way. Instead Paul’s work invites and entices the eye to look through the hourglass and fall into an alternate state of perception. He is not interested in giving you a linear narrative, in fact it matters little to him what you see. People see things differently. His work is an investigation of visual stimuli from his environment, memories and experiences, sensations and thoughts. A couple of years ago Paul was recovering from meningitis, he tells of how he noticed pattern in an intensified way.

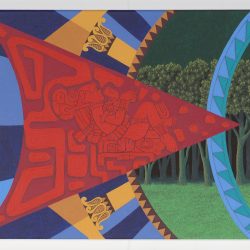

It is not improbable that his brain changed the way he sees things. In his paintings he intensely studies the pattern structure and colour composition of images and aspects of his lifestyle that has an impact on his sense of awareness. Once on canvas these studies dissolve and become irrelevant. What becomes relevant is the skillful and well mastered practical application of precious paint onto carefully prepared surfaces. Instead of soundwaves moving you, acute colour waves come at you.

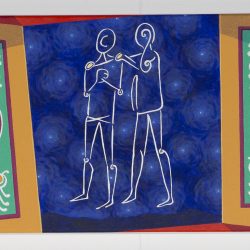

Many of the paintings in this show make you feel like you are around a campfire being told some late-night tales. There are suggestions of unseen auguries beneath the appearance of things, A peculiar comfort and angst, a push and pull that is simultaneously stimulating and disconcerting.

“Flying Dream” a small unassuming work exemplifies this. The dreamer is locked away in sleep in his own frame, unlike “the Artist” that takes centre stage. The rest of the work is a view over the roof tops of Auckland houses. The familiar landscape you would see on any Grey Lynn on Ponsonby street. You look wanting to recognize a specific place to ground your direction, but the apocalyptic night streets in deep azures and cobalt gleam steers you to the open door, the house with the light on beckoning you to enter. You will be safe here you think, but it’s so small, it’s so pretty. It’s just paint on canvas. It is not real. The canvas surface, under Paul’s hand becomes an imagined plane that is malleable and moves in a mind. The house, the dreamer, the streets are not there physically at all. It is an illusion. Philip Guston had this figured out when he said: “Painting is an illusion, a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see.

Paul uses colour and form with such articulation, he tricks the eye like a magician. He’s not telling you the story; or where you should go, you are making it up. He doesn’t provide the representational narrative as such, but rather a fastidious technical application of medium and skill. Like Timothy Leary, he just opened the door.

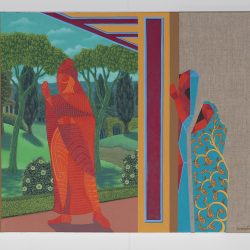

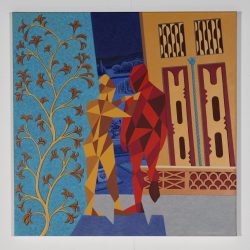

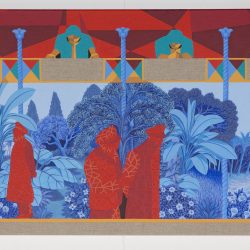

Not dissimilar to De Chirico whose best-known works are the paintings of his metaphysical period, Paul also exhibits a repertoire of motifs. Like the angular veiled priestesses, architecture and New Zealand vegetation. Doorways and windows function as visual tropes that allow for the sense of passage or movement from one realm of consciousness into another. There is a flirtation between contrasting scenes within one frame.

The body of work that Paul produced for Articulate Silences explores the unconscious dream scape pulling and pushing between geometric and botanical forms. The real and the imagined, the conscious and the unconscious invasively encroaching on each other’s territory with curious voyeurism and ominous desire. He manages to achieve a vertiginous attraction to and aversion by sharp bright motifs. The colours and stark planes have a sexiness, riskiness, rebelliousness against conformity and composition, while simultaneously these same aspects explore innocent curiosity and childlike adventure.

There is a lot going on, but like De Chirico Paul is interested in the investigation of the unexpected sensations that familiar places or things evoke, fusing everyday mundane with mythology and madness that conjures inexplicable moods of nostalgia, tense anticipation, and estrangement. That is Punk!

Janie van Woerden. April 2020.

1. Simon Riggs : http://simongrigg.info/zwines.htm

2. Kerry Buchanan in his notes to the long unavailable compilation Move to Riot.

3. Richard Kearney (2001) The God That May Be: A Hermeneutics of Religion. Indiana University Press: Bloomington